News & Insights |

Businesses grapple with the best way to prevent, address, and respond to harassment in the workplace. The law provides guidance. Policies, training, complaint procedures, and investigation protocols--all suggested or required by law to avoid liability for harassment--are not hard to come by. But while legal compliance is generally an attainable goal, it does not prepare businesses to truly engage in the process most influential on how workers treat each other: the development of workplace culture. When people think of sexual harassment, they usually think of explicit sexual innuendo, inappropriate and unwanted flirting, procuring sexual favors for workplace benefits, and unwanted physical touching of gender-specific body parts. Under the law, an illegal hostile workplace environment exists only when the sexual harassment is “severe and pervasive.” From a social and psychological perspective, harassment is more complicated. Sexual harassment is not simply a reflection of desire or insufficient social skills. Harassment based on sex—or race, religion, or other aspects of identity—is an exertion of power and exclusion. It makes the target feel uncomfortable, ashamed, confused, scared, or hurt. It works to denigrate, exclude, and push down people based on their identity. Harassment occurs in many ways. Harassment can:

All of these forms of harassment alienate and harm people—both the target of the harassment and the people around them—and the environment in which they exist. Impact on people:

Impact on business:

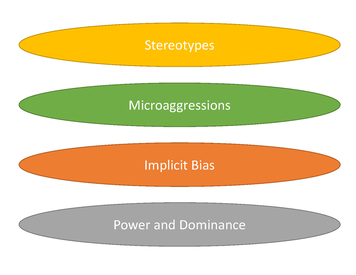

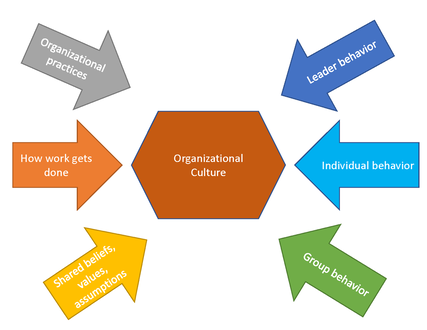

The law does not make all harassment illegal. In 1998, for example, the Supreme Court held that "simple teasing, offhand comments, and isolated incidents (unless extremely serious)" do not create a hostile work environment based on sexual harassment in violation of Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964. And it has long held that Title VII is "not a civility code." That is still the law. But as our society begins to more comprehensively understand the impetus behind harassment--again, not just sexual harassment but racial as well--it becomes more complicated to label something "simple teasing." And we know that "low grade harassment" such as "simple teasing" still alienates and harms the harassee and environment. . This is particularly true at the workplace. Employed persons often spend the majority of their waking hours at work interacting with others. Workplace culture and relationships are foundational to working persons' lives and experiences. No employer or business wants its employees to feel they do not belong or are not valued. Not only is it bad for the elusive bottom line, it is just bad for people. The law of sexual harassment and discrimination is only one rough tool to address workplace harassment. In Harassment, Workplace Culture, and the Power and Limits of Law, 70 Am. Univ. L.R. 419 (2020), Professor Suzanne B. Goldberg presents a compelling and easily read analysis of how the law can help and how it cannot. For example, harassment that does not create legal liability still negatively affects targeted employees and the broader workplace. As she explains: "The problem is that an approach delinking legal accountability from workplace culture misses the ways in which choices about compliance can create additional barriers to effective harassment prevention and response... Harassment policy, communications, and trainings are elements of culture-creation, not just protection against liability. When they are generated and implemented through a compliance lens, employers may satisfy their general counsel but will be unlikely to improve the experience of employees, except perhaps at the margins." When making choices about how to address and respond to harassment, businesses often make choices based on legal accountability rather than cultural development. Empirically, cultural development ultimately bears the strongest influence on employee behavior.  For example, organizational culture can create an atmosphere in which harassment is not understood or proscribed. As a result, sexual harassment historically and currently often goes underreported. Targets of harassment may refrain because of shame, embarrassment, or self-blame; for fear of retaliation or further marginalization, or based on their belief the organization will not be able to help them. This is is particularly true for more vulnerable persons at work: low-level supervisees, individuals depending on their employment for immigration status, or workers dependent on their job for basic subsistence. Likewise, organizational cultural expectations teach employees how to treat each other. These expectations are created not just at the top by business leaders but throughout the organization at all levels. How the organization responds to bad behavior or complaints also creates a cultural understanding and expectation. What this all means: creating a legally compliant harassment policy, complaint procedure, investigation protocol, and outcome expectations will satisfy the law. It also contributes to the overall organizational culture that more directly influences employee behavior. As Professor Goldberg advises: "By seeing harassment prevention and response as an opportunity for culture creation in addition to being a compliance obligation, it also becomes clear that harassing behavior may negatively affect the targeted employee and the broader workplace even when there is no risk of liability. This includes 'low-grade harassment,' a category I use to describe behaviors that are intentionally harassing but not severe or pervasive enough to meet doctrinal thresholds. Also relevant are microaggressions and interactions that reflect implicit bias, as these are unlikely to expose a firm to liability because they lack the discriminatory intent required by legal doctrine but nonetheless can create significant challenges for employees and organizations. This is not to suggest that employers should respond in an identical way to all of these occurrences. Rather, the point is that inattention to experiences that go beyond legal-accountability requirements is likely to spill over into the broader workplace culture and diminish the effectiveness of other harassment prevention and response efforts." |

|

714 W. State St.

Boise, ID 83702 |

©2024 Dempsey Foster PLLC. All rights reserved.